Energy Institute Blog

Research that Informs Business and Public Policy

Provocative new research delivers a carbon offset reality check.

There’s lots to unpack from the COP26 meetings in Glasgow. One development that has economists talking is an agreement on how countries can work together to meet their emissions reductions targets. After years of gridlock, negotiators managed to hammer out consensus language that allows countries to partially meet their targets with cross-border transfers of carbon offsets.

This may sound like blah blah blah. But a centralized system for compliance offsets could channel trillions of dollars into forestry projects, renewable energy in emerging markets, and other mitigation investments. If done right, this will significantly reduce the global costs of climate change mitigation. If done wrong, low-quality carbon offsets could undermine real progress towards national climate commitments.

Skeptics are right to be concerned about the worst-case scenario. In contrast to carbon permit markets, where emitters must pay for carbon emissions that can be directly measured, carbon offsets award credits on the basis of emissions that would have happened absent the offset transaction. This is a tricky accounting exercise. Partly because it involves estimating highly uncertain outcomes. Partly because both sides of the transaction have an incentive to over-estimate emissions reductions.

This week’s blog digs into some new research that finds evidence of significant over-crediting in two of the world’s most important compliance offset markets. These findings are discouraging. But I see some room for optimism. With new data and new analytics, researchers are devising new ways to carefully evaluate the GHG impacts of offset projects. Along with sobering punchlines and cautionary tales, this work could provide inspiration for future offset protocols that incorporate rigorous project evaluation before carbon offsets are awarded (versus after the carbon offset horse has left the barn).

To see how this might work, let’s dig into the research. First stop, India.

Wind energy offsets in India

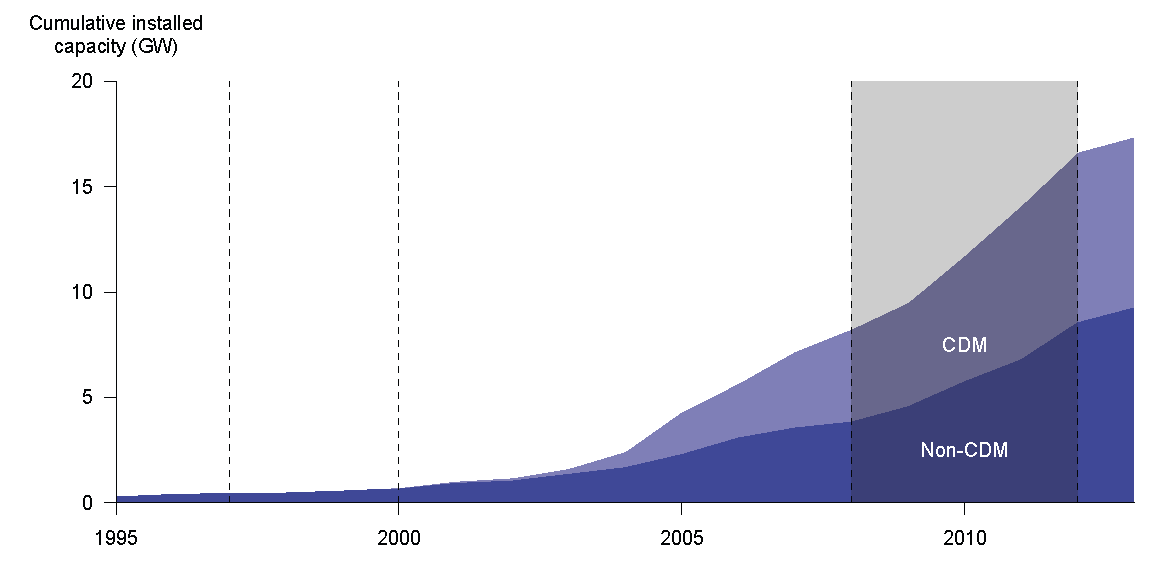

The first paper takes a deep dive into the world’s largest GHG offset program. Under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), industrialized countries could meet part of their Kyoto protocol emissions reduction obligations by subsidizing emissions reductions in other countries. Source

Source

Allowing countries to offset some of their own GHG emissions with credits purchased from CDM projects presumes that the CDM projects actually deliver additional (and permanent) GHG reductions. To qualify for CDM credits, CDM projects have had to demonstrate that the investment would not/could not happen without the CDM subsidy. In other words, they must demonstrate that the project is marginal.

With the benefit of hindsight, these authors assess the evidence on whether CDM projects have in fact been marginal projects. They focus on wind power in India where many projects have been supported by CDM.

Wind capacity investment in India (Source)

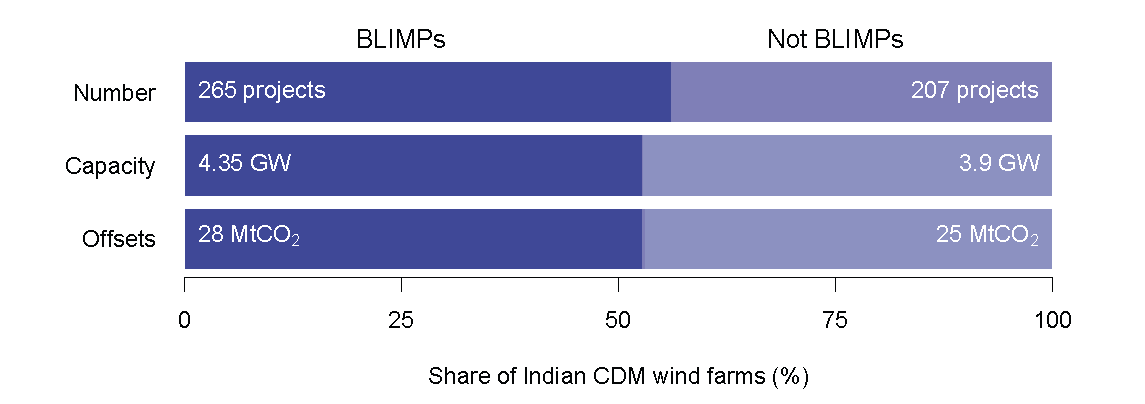

The authors argue that, if a CDM wind project is marginal, we should not see less productive wind projects built in the same state and year without CDM subsidies. Armed with this insight, they compare each of the 472 CDM wind projects in India against unsubsidized wind investments. They find that they can match over half of CDM wind projects with at least one unsubsidized project built in the same state and year. Furthermore, the unsubsidized projects are less productive and further from the transmission network. They label these non-marginal CDM projects blatantly inframarginal (BLIMPs). The authors interpret their BLIMP findings as evidence of substantial over-crediting:

Fortunately, offset accounting protocols have improved since the days of CDM. Rather than rely on suspect claims made by project developers, some newer protocols assess carbon emissions impacts by comparing a project’s emissions profile against a standardized baseline. To see how this is working, let’s head to California…

Forest offsets in California

California’s GHG cap and trade program regulates emissions from industrial sources like refineries and power plants. These sources can meet part of their compliance obligation using registered offsets. Almost 200 million offsets have been issued so far under this California program. The majority aim to reward improved forest management practices that increase the amount of carbon stored in forests.

California’s compliance offset protocol is far too complicated for this economist to deeply understand (let alone unpack in a blog). But there are three details that are important for this story. First: the majority of forest offset credits are awarded upfront based on carbon stocks surveyed over an initial reporting period. Second: the number of carbon credits awarded is largely determined by the difference between surveyed carbon stores and a standardized baseline. Third: standardized baselines are based on coarse regional averages that span a wide range of forest types. Source

Source

A significant concern with this approach is that forest types can vary a lot in terms of naturally occurring carbon stocks. Forest plots that naturally outperform the average can earn offset credits for doing what they would have done anyway. And because forest managers presumably know a lot about their trees, we might worry that these natural outperformers will be the ones chasing the offset credits.

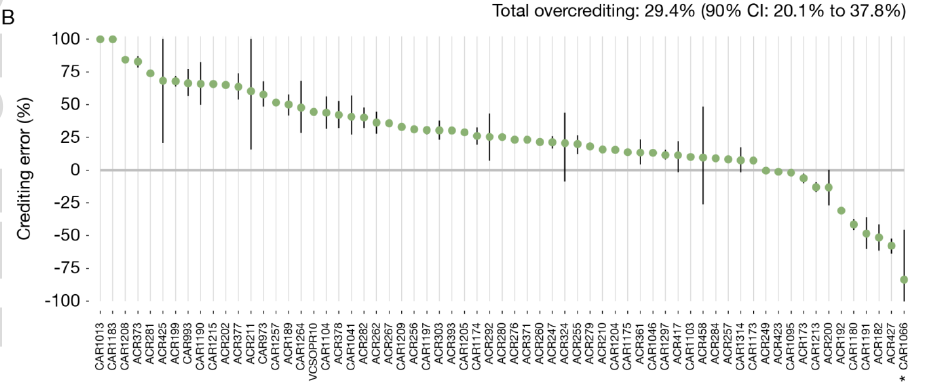

A new paper brings rich data to bear on this adverse selection concern. The authors develop a data-intensive approach to estimating project-specific, ecologically grounded, common-practice baselines. Using information about the species composition of each offset project, they re-calculate the number of credits that a project would have received if it had been evaluated against the more rigorous benchmark. They compare this number against the credits that were actually awarded.

The figure summarizes the extent of over- and under-crediting as a percentage of actual credits awarded to each project. Circles indicate each project’s median estimate. Positive crediting errors indicating over-crediting and negative crediting errors indicating under-crediting. The lines indicate confidence intervals.

The authors estimate that almost 30 percent of the forest offset credits allocated are rewarding naturally occurring differences in carbon stocks versus additional climate benefits. If you want a deeper dive into these results, data and code are available here.

Of course, adverse selection is not the only concern in play. Other concerns ( e.g. Are credited reductions permanent reductions? When does common practice represent the true baseline? Are carbon stores the best measure of climate benefits?) are much harder to pin down empirically. So this paper cannot offer a comprehensive measure of the climate impacts of forest offset projects. But it does provide a valuable reality check on our offset accounting protocols.

Project evaluation when it counts

From wind farms in India to forests in California, researchers are finding that compliance offsets are not delivering all the GHG emissions reductions they are credited for. Unfortunately, under existing protocols, this diagnosis comes too late. By the time the evidence is in, offset credits have already been issued (and possibly used to permit GHGs somewhere else).

Does it have to work this way? What if more rigorous empirical analysis happened before the carbon offsets were awarded? What if, whenever possible, ex post empirical evaluation of project-level GHG emissions impacts was a pre-condition for carbon offset crediting?

Requiring more rigorous and detailed project evaluation before offset credits are issued would make the process more onerous and involved. But it could also make the credits more credible. If we’re going to lean on carbon offset programs to meet our climate mitigation goals and incentivize future investments in global climate change mitigation, we need to get better at targeting these incentives. We are developing the tools to do better. Let’s figure out how to use them when it counts.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Fowlie, Meredith. “Carbon Offsets Get a Green Light in Glasgow” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, November 22, 2021, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2021/11/22/carbon-offsets-get-a-green-light-in-glasgow/

Categories

Uncategorized

Tags

carbon pricing, climate change, emissions market, greenhouse gas, renewable energy

Two more links questioning the effectiveness of current carbon offset programs….

The Climate Solution Actually Adding Millions of Tons of CO2 Into the Atmosphere

by Lisa Song, ProPublica, and James Temple, MIT Technology Review

https://www.propublica.org/article/the-climate-solution-actually-adding-millions-of-tons-of-co2-into-the-atmosphere

Systematic over-crediting of forest offsets

https://carbonplan.org/research/forest-offsets-explainer

Carbon offsets are widely used by individuals, corporations, and governments to mitigate their greenhouse gas emissions. Because offsets effectively allow pollution to continue, however, they must reflect real climate benefits.

To better understand whether these climate claims hold up in practice, we performed a comprehensive evaluation of California’s forest carbon offsets program — the largest such program in existence, worth more than $2 billion. Our analysis of crediting errors demonstrates that a large fraction of the credits in the program do not reflect real climate benefits. The scale of the problem is enormous: 29% of the offsets we analyzed are over-credited, totaling 30 million tCO₂e worth approximately $410 million.

A good idea in theory to reduce the cost of compliance, but in reality too difficult to measure, track, and verify and too easy to game the system.

Also what happens when the forest fire burns the offsets? Does the offset purchaser now need to buy more offsets to compensate?

The other side of the green-paradox coin is the temptation to over-deforest now in order to get larger reforestation benefits later. As indicated, this can be avoided by a “more rigorous benchmark.” A natural candidate for that baseline is the forest practice that would obtain under profit maximization absent any carbon pricing. The baseline doesn’t have to be precise to avoid perverse incentives. The important thing is that it can’t be manipulated.

Inasmuch as a substantial share of timber harvests is “pickled” (in lumber and other slow-decaying wood products), net carbon sequestration is not maximized by storing as much carbon as you can in trees (preservation). Rather, a positive stream of net sequestration can be sustained indefinitely.

CDMs are fine if there are strong monitoring controls. There is enough corruption in many countries so that a ‘clean’ plan could be shown, but never executed. I the meantime the ‘developed-county’ company essentially ‘bribes’ a ‘developing-country’ business and/or bureaucrat for the offsets. The incentive and the cost should be processed separately through a trustworthy bureaucracy.

With the inevitable ‘working of the system’ will come little to no real action to avert the effects we are already seeing on earth’s climate.

That’s why in addition to ‘Carbon Offsets’ we are going to need a ‘Carbon Fee And Dividend’ asap.

Visit Our Website

Join Our Email List

Donate Today

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to the author and the Energy Institute with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.