Copy link to share with friends

By Tom Cassauwers

Copy link to share with friends

Open-source software has an image of radicalism. Yet it’s increasingly an ally — not enemy — of big tech.

By Tom Cassauwers

When Vicky Brasseur, known as VM Brasseur online, got into open-source coding more than 30 years ago, the name hadn’t even been invented yet. She worked on initiatives like Project Gutenberg as part of what was then called the free culture movement, whose goal was for information to be free, and software democratic.

Today, Brasseur isn’t a fringe activist or hacker. She is director of open-source strategy at Juniper Networks, a U.S. corporation with approximately 10,000 employees.

Brasseur personifies the dramatic change in what is now known as the open-source software movement. The words “open source” still call up images of radicals battling faceless corporations, of OpenOffice and Linux offering alternatives to giants like Microsoft. In 2000, Steve Ballmer, then director of Microsoft, even criticized Linux as “communist.”

Most modern software and cloud products are built on top of open source.

Karl Popp, SAP

But more and more large corporations are embracing open-source software, which undergirds many of the commercial services we use every day. By 2016, when Microsoft moved part of its database infrastructure to Linux, Ballmer had backed off from his open-source-as-communism stance. Two years later, in 2018, Microsoft bought GitHub, a code-sharing site for open-source projects, for $7.5 billion. MySQL, an open-source system for building databases, is used by Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. And amid the coronavirus pandemic, pharma giant Pfizer has announced that it is using an open-source platform to share its research findings with other companies to hasten the global race for a vaccine.

“There’s hardly any commercial product available today that doesn’t use open source,” says Karl Popp, an expert on open source at German software corporation SAP. “Most modern software and cloud products are built on top of open source.”

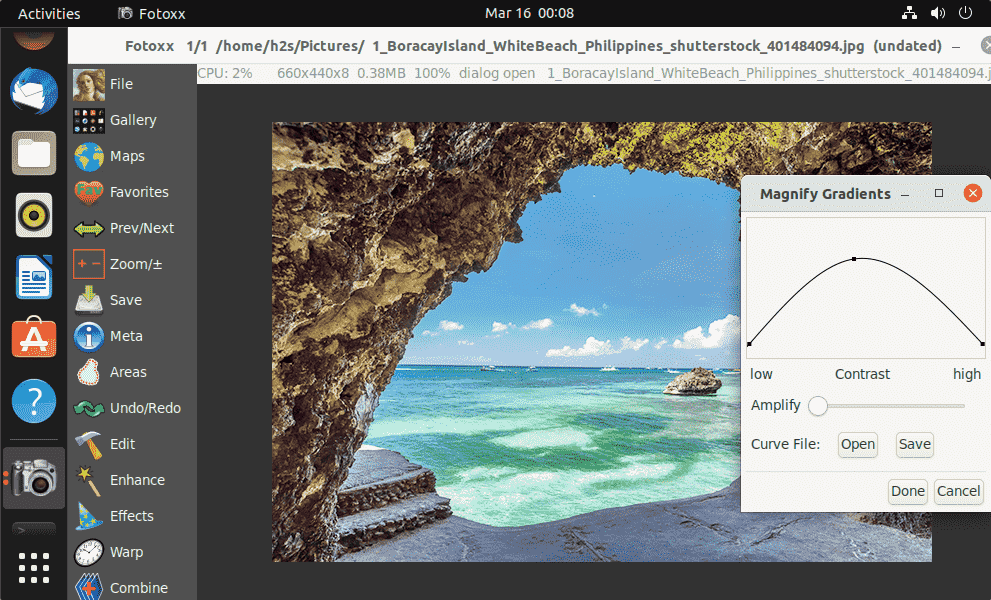

Odoo open-source customer relationship management software.

Smaller firms are also using open-source coding as a business model. Belgian startup Odoo offers both a free open-source enterprise software system and a paid-for version with extra features. “Initially it wasn’t a conscious strategy to go open source,” says Fabien Pinckaers, Odoo CEO and founder. “I was just passionate about open source when I was young, and it developed from there.”

And going the open-source route isn’t a bad idea financially. Odoo, which employs 800 people and has more than 4.5 million users, has raised over $100 million in venture capital. High-end acquisitions aren’t out of the question either. In 2008, Sun Microsystems bought the company behind MySQL for $1 billion. Whether startup or corporate giant, open source increasingly means big bucks.

That shift has its critics. “The degree in which corporations knowingly and openly use open source has grown,” says Karl Fogel, a developer and open-source advocate. Still, some open-source developers feel that although these businesses build a lot of value on top of their work, they’re not seeing “enough of it flowing back to them,” Fogel says.

But the narrative of a noncommercial open source being colonized by the corporate world also has its flaws, cautions Fogel. Open source has always been commercial to a certain degree. Even in the more radical currents of the movement, where the term “free software” is preferred over open source, making money isn’t necessarily shunned. Richard Stallman, one of the movement’s pioneers, famously said that the “free” in “free software” should be taken as “free speech, not free beer.” All the talk about freedom and digital self-ownership doesn’t preclude making money.

Nevertheless, open source and making money still clash at times, something Pinckaers learned firsthand. Odoo started out as a completely open-source project. When certain features were made paid-for, proprietary services as part of a change in the company’s business model, it sparked an outcry among members of the Odoo community. “We won’t change the fact that we are open source,” says Pinckaers. “But in the past we didn’t make our business model sufficiently clear from the beginning. Which was a mistake that caused a lot of frustration in the community.”

Businesses also sometimes free ride on the work of volunteer contributors. “People in the free software movement might not like this statement,” says Popp, “but open source allows you to outsource development and maintenance to a community at zero cost.”

In this way, open source becomes a cheap outsourcing opportunity for large companies. When the so-called Heartbleed bug was discovered in 2014 in the open-source OpenSSL cryptography library, which secures a substantial part of the internet, the fact that the bug had remained undiscovered for so long was traced back to underfunding and developer burnout. OpenSSL co-founder Steve Marquess subsequently placed some blame on “Fortune 1,000” companies that used the system but refused to give anything back.

There are ways to balance this relationship, says Brasseur. “Corporations need to be good citizens,” she says. “Some companies will use open source without giving back. But we shouldn’t just attribute this to malice. Often they don’t know any better. We should educate them so they also contribute back to these projects.”

Which many already do to a degree. Today, corporations even fund open-source projects and allow their own programmers to contribute to them on company time. “SAP gives massive donations to open-source projects by having our developers work on them,” says Popp. “And in this way we can work together with the community, because they develop the software much faster than a single company would be able to do.” Google is a platinum member of the Linux Foundation, which comes with a $500,000-a-year price tag.

And for all the commercialization, Fogel says, the original spirit of open source remains alive. “The original free software and open-source ethos has become more widely known and believed in today,” he says. “Everyone uses digital devices and is aware of problems like privacy. Which has allowed for a flourishing of the mindset that our tools should work on our behalf, not someone else’s.” Corporatized open source hasn’t lost its principles yet.

The Best New Trends of 2017: As cryptocurrencies and blockchain grow, so, too, does cryptocrime.

Open borders? Nope.

Forget tour groups — Chinese travelers are renting RVs and setting off to see the sights.

Christina Sass’ quest to reimagine education has landed her in Africa, with a whopping investment from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

Respected chefs open a new restaurant in LA’s Watts neighborhood.

This new tech can identify missing pooches by their mug shots.

Did you remember to close the garage door? Now you can check with your smartphone.

Meet ALICE — the fancy mobile technology behind the scenes at some of America’s swankiest hotels — and the guy who helped create her.

A man with an unlikely expertise is trying to lead an even more unlikely revolution in physical therapy and rehab.

Most of us still don’t have a clue about the IoT.

This 12-year-old boy, with an eye on making life easier for the blind, might just be a future Silicon Valley entrepreneur.

Cyberassailants are turning to infiltrating infrastructure systems like gas lines and power grids.

One island, one town, 150 graffiti artists and 30 nationalities all make for one hell of a street museum.

Meet the tech star turned public servant working to make Estonia the world’s most digitally advanced country.

This Dutch designer turned entrepreneur is determined to expose the murky supply chain behind your smartphone and offer you a guilt-free alternative.

© OZY 2021 – Terms & Conditions